Immigrant families separated during President Donald Trump’s first term, once a potent symbol of harsh government overreach, are facing new legal obstacles from an emboldened second-term Trump administration.

Legal Obstacles and Conflicts

It’s an unusual predicament: The same administration that has been trying to deport them is now trying to take over the responsibility for guiding them through complex legal proceedings in immigration court.

The Justice Department says it’s about efficiency. Advocates and independent lawyers who have worked with the families call it an obvious conflict of interest. The issue will come to a head in a hearing scheduled Friday.

Challenges from Settlement

The latest clash stems from a 2023 court-approved settlement aimed at supporting the families separated by Trump’s immigration policies in 2017 and 2018. The settlement required the administration to provide a wide range of benefits, including government-funded legal services.

Until May 1, the families had been receiving legal support from outside groups, led by the Acacia Center for Justice, a nonprofit immigrant legal defense organization. These independent lawyers have helped them navigate the byzantine process of reunifying, applying for temporary legal status and deciphering immigration court — until the Justice Department abruptly declined to renew the contract with Acacia.

Concerns and Warnings

That decision to move the legal services in-house has left advocates for these separated families alarmed, baffled and warning of an inherent conflict. Not only was the cutoff of Acacia’s services abrupt, they say, the administration provided no roadmap for how it will take over the legal cases for up to 8,000 people, some of whom are facing urgent court deadlines and imminent deportation or separation once again.

This time, the world isn’t watching.

Future Implications

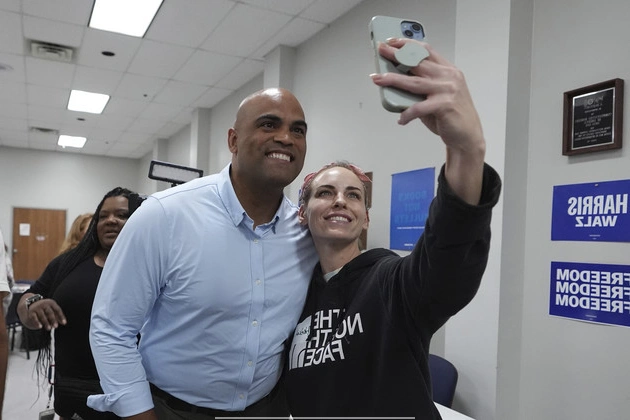

Their cases once drew intense national attention and visits from Democratic presidential contenders. But that has subsided as Trump’s second-term immigration agenda — including deportations to El Salvador’s mega prison and a slew of other legal battles — has overtaken interest in their plight. Advocates worry the diminishing attention will have real-world consequences for families as they attempt to resist new deportation efforts.

“Haven’t we put these families through enough?” said Anilú Chadwick, the pro bono director at Together & Free, a group that has worked with separated families. “I’m taken back to seven years ago when I was holding babies and trying to find their parents. It’s just unbelievable.”

A DOJ official said in a statement to POLITICO that it’s “insulting to suggest” that the department’s immigration office, “which is comprised of neutral, trained professionals and experts in immigration law, cannot provide services more effectively and efficiently than a self-interested, third-party outside contractor.”

Legal Aid and Settlement Terms

The separated families’ right to legal aid stems from a 2023 legal settlement overseen by U.S. District Judge Dana Sabraw. The Southern California-based appointee of George W. Bush approved an agreement requiring the federal government provide a range of services for parents and children separated by the Trump administration in 2017 and 2018, from medical care to housing support. The government also had to help the families work toward reunification and temporary legal status in the U.S., as well as provide legal services to help them navigate the complicated paperwork required to gain temporary legal status and access benefit programs.

The settlement required those services to be “adequately resourced and funded.”

Government Response and Justification

The Trump administration contends there has been no lapse in legal services and that replacing the contractors’ outside lawyers with its own in-house services satisfies the requirement of the settlement. Justice Department lawyers said the settlement also “does not require Defendants to provide legal services through the same method for the term of the agreement.”

DOJ lawyers also said in court filings that its Executive Office for Immigration Review would provide legal services to “maximize efficiency” — adding that by May 15, it would “begin providing regularly scheduled group sessions and self-help workshops” to “equip them with the knowledge and information to successfully navigate their immigration proceedings.” The department intends to lean on other contractors employed by the departments of Health and Human Services and Homeland Security to fill in other gaps in services.

In addition, DOJ’s immigration office “will leverage its existing pro bono network,” to connect “interested class members with pro bono representatives to provide representation,” the lawyers wrote.

Immediate Concerns and Risks

Advocates say this puts separated and reunified families in an impossible position: taking legal advice from the very government they are litigating against to obtain benefits.

A Tuesday court filing from American Civil Liberties Union lawyers identified 187 class members who could lose their humanitarian parole status and work permits in May, 113 in June and another 142 in July. Advocates are also tracking 114 class members who have active removal orders and who “urgently need access to legal services to file motions to reopen and dismiss their proceedings.”

The immigrant families “are being told that they have to go to the government, who harmed them and who is going to be adjudicating their cases, for confidential advice about what to do,” said Sara Van Hofwegen, managing director of legal access programs at Acacia. “There is immediate harm this week and next week, and in the months to come.”

Judicial Oversight and Future Actions

Sabraw, so far, is not crying foul. The judge said the concerns about inadequate representation by the government are speculative, and he could intervene in the future if there is evidence that families protected by the settlement are suddenly missing court deadlines or facing other hurdles due to the change in their legal services. He has called a hearing Friday to further air concerns about this new arrangement.

Acacia’s contract with the Justice Department, which began in May 2024, formed the Legal Access Services for Reunified Families program. The organization has overseen the program since, distributing the funding to subcontractor organizations across the country who have managed thousands of individual cases.

Acacia was in active talks to renew the contract with the Trump administration earlier this year, and staff members were stunned by the DOJ’s decision, Van Hofwegen said.

“We’re having to have conversations letting people know that we will no longer be a provider without being able to tell them about an existing plan,” said Emma Wilson, the program manager at ISLA Immigration, one of the subcontractors that provided legal services under the contract.

In court filings, advocates say they are already aware of class members who have been detained, including a separated child and multiple separated parents who have been unable to access legal services. They warn that these families could turn to predatory attorneys charging high fees in return for incomplete, sloppy paperwork.

“All of this is happening at a time of extraordinary immigration enforcement,” said Kelly Kribs, an attorney and co-director of the technical assistance program for the Young Center for Immigrant Children’s Rights, a group that has worked with hundreds of separated families since Trump’s zero tolerance policy. “These class members … are very much at risk of detention and potential deportation.”