HUNTINGTON BEACH, California — Southern California’s newest political movement meets on Saturday afternoons with paperback novels and lawn chairs outside the local public library.

In this well-to-do enclave known equally for its nickname of “Surf City” and its far-right politics, progressive activists and book lovers have joined forces behind a pair of charter amendments that would wrest control of the local public library system away from a MAGA-aligned city council playing an increasingly active role in managing its affairs.

Library defenders in Huntington Beach are taking their fight to the ballot as public libraries have become a conservative culture-war target across the country. In statehouses, on local ballots and even at the Library of Congress, Republican politicians are working to cut funding, remove controversial books and fire or even seek criminal charges for librarians who provide certain content to children.

The Library Left’s Strategic Gamble

Now it’s the library left that’s fighting back. Our Library Matters, the Huntington Beach campaign committee working to pass Measures A and B, is making a strategic gamble that it can convince voters in a deeply polarized environment to once again view their local library as anodyne if not beloved civic furniture rather than a culture-war battleground. The opposition is not making that easy, putting up campaign posters around the city — including next to public schools — that read, “PROTECT OUR KIDS FROM PORN, NO on A & B.”

Challenges Facing Public Libraries

The campaign unfolding before the June 10 vote is being tracked around the country as librarians and library boards rethink the way that they engage in politics.

“We’re watching Huntington Beach closely,” said Deborah Caldwell-Stone, the director of the American Library Association’s Office for Intellectual Freedom. “We’ve traditionally looked to the courts to preserve our civil liberties, but in a time when litigation takes years, it might be more effective to go to the ballot box … to preserve the freedom to read and prevent censorship at local libraries.”

The road to the ballot begins on the top floor of Huntington Beach’s Central Library, where a building elsewhere bustling with readers hunched over desks and families thumbing through picture books gives way to a mostly deserted set of stacks. On one of them, a shelf labeled “Youth Restricted Books” holds eight thin tomes. They include one titled “Sex Is A Funny Word” and another “The Care and Keeping Of You,” about puberty for girls.

Together the books take up just a few inches of shelf space, but they have cast a long shadow over the city’s politics. Last year, they were relocated from the library’s children’s section on the ground floor, after the city council took the authority to decide what went on library shelves away from librarians and handed it to an appointed board.

Supporters of the move, led by City Councilmember Gracey Van Der Mark, argued the creation of a Community Parent-Guardian Review Board would protect children from inappropriate content. “The whole goal,” Van Der Mark said after voting to create the board, is “to make our libraries the safest place for our children.”

The 21-member board was ordered to sign off on all new books acquired by the children’s section and review its existing holdings. Those that failed to win approval were banished to the restricted section.

A Political Shift in Huntington Beach

Huntington Beach has always been a conservative place, a haven for Reagan Republicanism just south of deep-blue Los Angeles County. But over the course of the last decade, the flavor of conservatism prevalent in the city’s politics has increasingly aligned with President Donald Trump’s MAGA-style politics.

Mirroring the issues championed by Trump and his allies on the national level, a newly elected conservative majority on Huntington Beach’s city council in 2023 declared it a “No Mask and No Vaccine Mandate” town. It banned the Pride flag from city buildings and city property. And it pushed a voter ID measure that voters approved in March 2024, putting the city on a collision course with state officials over its enforcement.

Then the conservative faction on Huntington Beach’s city council turned its attention to the public library system. Last year, months after establishing the parental review board, councilmembers raised the possibility of privatizing the library to cut down on costs. (They abandoned the effort after the company bidding on the project withdrew, amid public backlash.)

Protect Huntington Beach, an advocacy group which launched shortly after the 2022 election as a magnet for the city’s besieged progressives, folded the library issues into its work challenging many of the city council’s policies. The group loudly opposed three charter amendments that the council’s conservatives had placed on the March 2024 ballot, including one to require voter ID and another to limit which flags could be flown on city property.

Community Response and Activism

But the efforts to exert control over the public library also galvanized many residents far outside the usual political realm: teachers, parents and librarians who might not have seen themselves in some of the council’s other targets but viewed incursions into a treasured institution as a step too far.

Daus, a retired writer and editor who began volunteering at the library eight years ago, had remained silent during the council’s run through national “culture war issues.” But when she heard local officials were planning to interfere in what books the library could carry, she attended her first city council meeting in June 2023 to oppose it.

“That’s book banning,” she said. “I mean, they can fight it as much as they want, but it is book banning.”

Months after the city council approved the parental review board, a group of local library supporters and activists began charting a plan to push back. They would employ the same tool the conservative city council had used to implement some of its previous priorities — going to voters directly — to enshrine protections for librarians and the public library’s financing in the city charter.

Protect Huntington Beach activists teamed up with members from the nonprofit Friends of the Huntington Beach Public Library to gather signatures for two separate charter amendments. The first proposal, which became Measure A, would repeal the city council’s parental review board, handing control of library content back to public librarians. The proposal that is now Measure B would prohibit the city from selling or leasing parts of the public library system to private companies, or otherwise privatizing library services.

Protecting the Heart of the Community

“When this whole library thing blew up, it was twofold: It was our city finances that were going to be impacted [via privatization], and our city services,” Cathey Ryder, the organization’s co-founder, said ahead of a recent community walk event to raise awareness for the two measures.

Ryder said she and others involved in the signature-gathering efforts had fully expected the two measures to wait for the 2026 ballot. They were surprised when the city council, after acknowledging in January that the measures had gathered enough signatures to qualify, would come before voters this year as the only two items in a June 10 special election.

“For reasons unbeknownst to us, the city has opted to go this route,” she said. “My suspicion is that they’re expecting low voter turnout.”

National Implications and Challenges

The move to the ballot represents a new front in a rolling conflict over libraries begun by Trump-aligned conservatives who have taken aim at the institutions as emblematic of what they see as a broader liberal takeover of national discourse, particularly when it comes to LGBTQ+ topics.

In the introduction to Project 2025, the conservative blueprint that has served as the foundation for much of the Trump administration’s early policy actions, Heritage Foundation President Kevin Roberts alleges the nation’s public libraries are rife with pornography in the form of “transgender ideology and sexualization of children.”

“Educators and public librarians who purvey it should be classed as registered sex offenders,” Roberts wrote.

When Trump fired Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden earlier this month, his team justified it by saying she had been “putting inappropriate books in the library for children.”

The Trump administration has also targeted library funding as part of its quest to drastically cut the cost of the federal government. In a March executive order, Trump called for the elimination of the Institute of Museum and Library Services, which provides federal funding to libraries and museums around the country. (A federal judge halted that order in response to a lawsuit from attorneys general in 21 states, including California.)

Historical Perspectives on Library Resistance

Public libraries, along with public schools and public universities, have faced different types of pushback at various points in their roughly 150-year history in the United States, said Steven Conn, a historian at Miami University in Ohio.

Some of that resistance comes from small-government conservatives who believe taxpayer money shouldn’t be used for things like libraries. Another strain of opposition, the one Conn says is at play today, stems from a “moral panic” and unease with the direction of the country or the pace of social change.

“Libraries become a target when people are feeling particularly anxious about the state of the world and they’re frightened for their children,” said Conn, noting that whether it was comic books in the 1950s or LGBTQ+ friendly books today, anxious parents worried the library was the source of “toxic” materials for their kids. “We use our children to fight our proxy battles for us — that’s also a long tradition in American history.”

Current Challenges and Advocacy

The ALA’s Caldwell-Stone said the current wave of efforts to target library content and politicize the institution have picked up significantly in the last five years. And the Chicago-based 501(c)4 advocacy organization EveryLibrary is tracking 130 bills moving through statehouses across the country this year that seek to restrict library funding, content or activities.

In a handful of cases, conservatives have used ballot measures to try and codify library restrictions. A two-year battle over the LGBTQ+ themed book “Gender Queer” in the Pella, Iowa, public library culminated in the city council placing a measure on the ballot to bring the library under the council’s direct control. The measure failed narrowly, in November 2023, after robust pushback from defenders of the library.

Call to Action: Protect Our Libraries

“Prior to the current issues around book bans, the fights would be between a vote Yes for the library and a vote No against taxes. We would see those played out in certain communities when there was an anti-tax movement that wanted to close or shrink the library,” said EveryLibrary executive director John Chrastka. “The systemic approach to trying to defund the library to get rid of the ‘groomers and pedophiles’ is a recent addition to that lexicon.”

That language was on display word-for-word at an early May meeting of the Huntington Beach city council. Among the dozens of public comments were many accusing city librarians of allowing children access to pornographic content.

“If you vote yes on this,” said one woman who waited in line for a minute at the microphone, “you’re either a groomer or a pedophile or both.”

One Saturday afternoon in April, the front lobby of the library’s Central branch displayed black-and-white photos from its opening day in 1975 to celebrate its 50th anniversary. Elsewhere in the library, things continued as usual: Craft-lovers used sewing machines and laser cutters to work on projects in the library’s maker space downstairs, and youngsters frolicked in a bookshelf-filled pirate ship in the children’s section.

Outside, the movement that qualified Measures A and B gathered to read and display their homemade campaign signs. The base of active supports for the measures skews older, female and retired — as Barbara Shapiro, a retired nurse who helped gather signatures for the two measures and is volunteering for the Yes campaign, put it: “mostly Baby Boomers.”

Those demographics help make the campaign efforts to support Measures A and B — the read-ins, the community walks, the canvassing efforts — feel far cozier than the average campaign event.

“We’re the people that have the time,” said Shapiro, who raised four children in Huntington Beach and helped gather signatures for the two measures. “We grew up in a time before computers and iPhones and iPads — the digital world — existed, and we feel that reverence of the library. We want to protect that, and we want to keep that sanctuary of books for our grandchildren.”

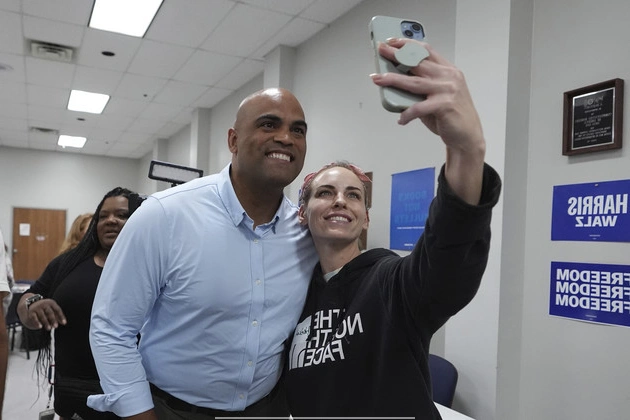

As the Yes side geared up for campaign mode, it has brought in outside help from Democratic campaign strategists and elected officials. Spencer Hagaman, a staffer in Assembly Speaker Robert Rivas’ office in Sacramento, left his post to move back to his hometown and run the Yes on A and B campaign. And Gina Clayton-Tarvin, a Democrat and member of the local school board, became an adviser to Our Library Matters shortly ahead of its official launch in mid-April.

“I want to make sure people understand this is not partisan to us,” said Clayton-Tarvin. “A library should never be made to be political. … This is about preserving what is good for our community.”

It’s crucial messaging in a city where Republicans have a 15,000-voter registration edge. In a low-turnout summer election, Measures A and B will likely need the support of city residents who voted for conservative members of the city council.

The No side, meanwhile, has doubled down on polarizing rhetoric. Opponents of the two measures have embraced the “groomers and pedophiles” language prevalent in library battles across the country, accusing the library of providing pornography for children and painting librarians as depraved purveyors of it.

“The people who are concerned about this word ‘porn’ being out in the public, I redirect your attention to the fact that this sexual content was pushed into the public library and that is what has pushed this into the public forum,” Chad Williams, the city council member who paid for the “Protect Our Kids from Porn” posters, said in a video posted to Facebook.

Williams and No side backers eventually removed some of the large posters due to parents’ complaints, but have repeated similar messaging on lawn signs and in mailers and brochures handed out around the city. “Shield Children from Pornographic and Inappropriate Content,” one mailer reads, over a close-up image of a young boy’s face. “Vote No on A&B — Protect Our Kids.”

If Our Library Matters hopes to bring down the temperature politically, the weeks leading up to Election Day have shown just how difficult a task that may be. The subject dominated an open-comment period at a recent city council meeting — held, ironically, in the library’s theater because of construction work at City Hall — with dozens of residents giving more than two hours’ worth of impassioned public comments on both sides to a room filled with Yes and No signs.

Leaders of the ballot campaign hope their read-ins, community walks and quirky and creative signs will mobilize the kind of voters who might not show up for a tense city council meeting. If they succeed, their strategy will serve as a potential model for besieged libraries around the country.

“Just let our library be a library,” said Shapiro. “That’s all we’re asking.”